What is I-Ching ?

The I Ching (Wade-Giles), "Yì Jīng" (Pinyin), also known as the Book of Changes, Classic of Changes; and Zhouyi, is one of the oldest of the Chinese classic texts.[1] The book contains a divination system comparable to Western geomancy or the West African Ifá system. In Western cultures and modern East Asia, it is still widely used for this purpose.

The standard text originated from the ancient text transmitted by Fei Zhi (费直, c. 50 BC-10 AD) of the Han Dynasty. During the Han Dynasty this version competed with the bowdlerised new text version transmitted by Tian He at the beginning of the Western Han. However, by the time of the Tang Dynasty the ancient text version, which had survived Qin’s book-burning by being preserved amongst the peasantry, became the accepted norm among Chinese scholars.

The earliest extant version of the text, written on bamboo slips, albeit incomplete, is the Chujian Zhouyi, and dates to the latter half of the Warring States period (mid 4th to early 3rd century BC), and certainly cannot be later than 223 BC, when Chu was conquered by Qin. It is essentially the same as the standard text, except for a few significant variora.

During the Warring States period, the text was re-interpreted as a system of cosmology and philosophy that subsequently became intrinsic to Chinese culture. It centred on the ideas of the dynamic balance of opposites, the evolution of events as a process, and acceptance of the inevitability of change.

The text of the I Ching is a set of oracular statements represented by 64 sets of six lines each called hexagrams (卦 guà). Each hexagram is a figure composed of six stacked horizontal lines (爻 yáo), each line is either Yang (an unbroken, or solid line), or Yin (broken, an open line with a gap in the center). With six such lines stacked from bottom to top there are 26 or 64 possible combinations, and thus 64 hexagrams represented.

The hexagram diagram is composed of two three-line arrangements called trigrams (卦 guà). There are 23, hence 8, possible trigrams. The traditional view was that the hexagrams were a later development and resulted from combining the two trigrams. However, in the earliest relevant archaeological evidence, groups of numerical symbols on many Western Zhou bronzes and a very few Shang oracle bones, such groups already usually appear in sets of six. A few have been found in sets of three numbers, but these are somewhat later. Numerical sets greatly predate the groups of broken and unbroken lines, leading modern scholars to doubt the mythical early attributions of the hexagram system,.

When a hexagram is cast using one of the traditional processes of divination with I Ching, each yin and yang line will be indicated as either moving (that is, changing), or fixed (unchanging). Sometimes called old lines, a second hexagram is created by changing moving lines to their opposite. These are referred to in the text by the numbers six through nine as follows:

Nine is old yang, an unbroken line (—θ—) changing into yin, a broken line (— —);Eight is young yin, a broken line (— —) without change;

Seven is young yang, an unbroken line (———) without change;

Six is old yin, a broken line (—X—) changing into yang, an unbroken line (———).

The oldest method for casting the hexagrams, the yarrow stalk method, was gradually replaced during the Han Dynasty by the three coins method and the yarrow stalk method was lost.[2] With the coin method, the probability of yin or yang is equal while with the recreated yarrow stalk method of Zhu Xi (1130–1200),[3] the probability of old yang is three times greater than old yin.

There have been several arrangements of the trigrams and hexagrams over the ages. The bā gùa is a circular arrangement of the trigrams, traditionally printed on a mirror, or disk. According to legend, Fu Xi found the bā gùa on the scales of a tortoise's back. They function like a magic square with the four axes summing to the same value, using 0 and 1 to represent yin and yang: 000 + 111 = 101 + 010 = 011 + 100 = 110 + 001 = 111.

The King Wen sequence is the traditional (i.e. "classical") sequence of the hexagrams used in most contemporary editions of the I Ching.So, it is the individual Chi of a person that leaves body after the death. At the same time, this individual Chi is a part of universal Chi of the world.

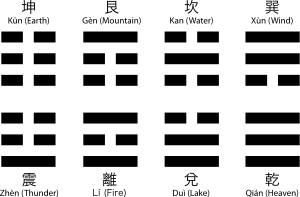

Trigrams

The solid line represents yang, the creative principle. The open line represents yin, the receptive principle. These principles are also represented in a common circular symbol (?), known as taijitu, but more commonly known in the west as the yin-yang) diagram, expressing the idea of complementarity of changes: when Yang is at top, Yin is increasing, and the reverse.

In the following lists, the trigrams and hexagrams are represented using a common textual convention, horizontally from left-to-right, using '|' for yang and '¦' for yin, rather than the traditional bottom-to-top. In a more modern usage, the numbers 0 and 1 can also be used to represent yin and yang, being read left-to-right. There are eight possible trigrams :